ACID vs BASE in databases isn’t just a theory battle — it’s a decision that shapes how banking systems keep your money safe or how Netflix never goes down on a Friday night.

Both terms show up in system design interviews, job descriptions for backend engineers, and even in real-world trade-offs companies make every single day. If you’ve ever wondered why MySQL feels rock-solid but Cassandra can handle insane scale — this is it.

Here’s the bold truth:

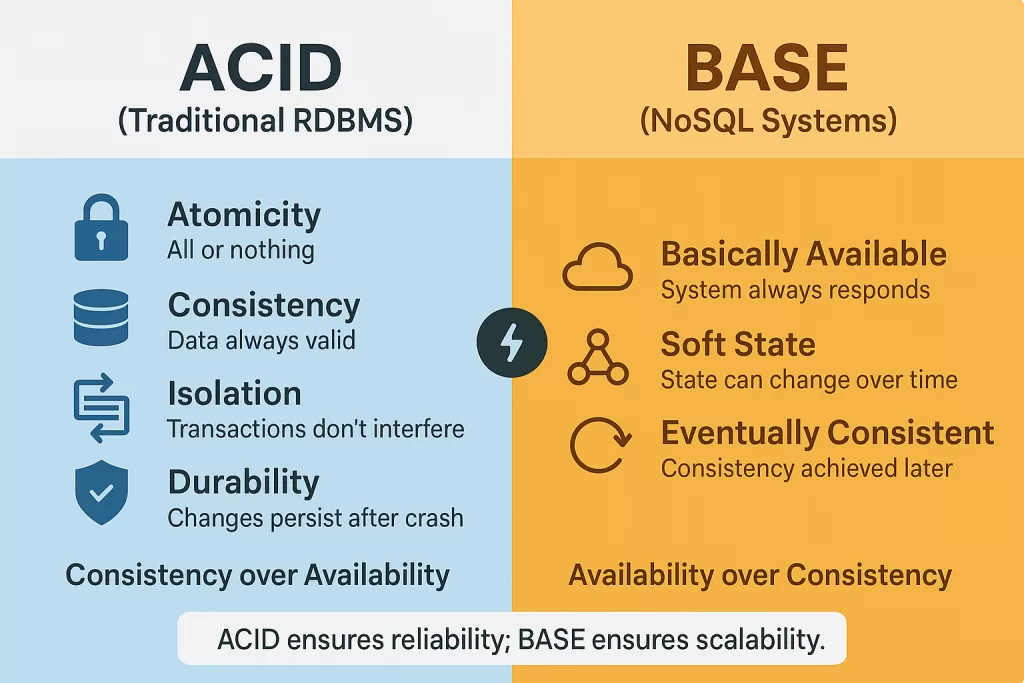

- The ACID model gives you consistency and reliability.

- The BASE model gives you flexibility and availability.

- Choosing between them is not about “right or wrong” — it’s about what your career and system demand.

⚡ Key Highlights

- ACID = Reliability & Consistency. Think banks, healthcare, transactions — systems where data integrity is sacred.

- BASE = Scalability & Availability. Think Amazon, Netflix, social media — systems where uptime and speed matter most.

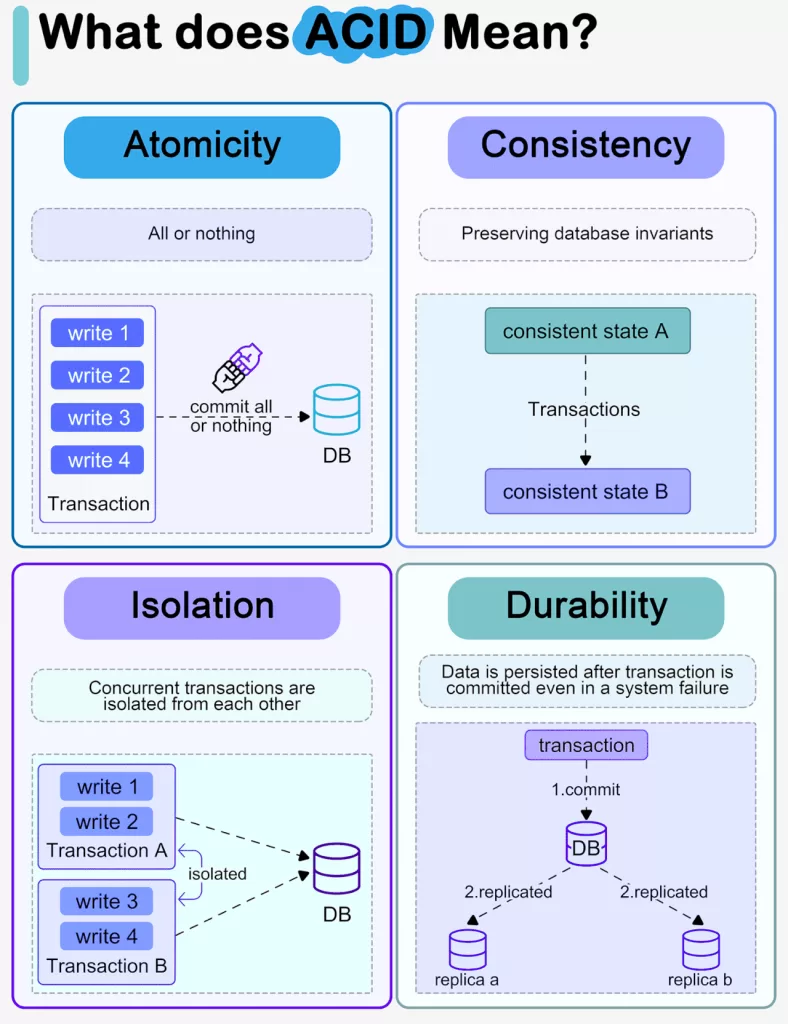

- ACID stands for: Atomicity, Consistency, Isolation, Durability — ensures safe, all-or-nothing transactions.

- BASE stands for: Basically Available, Soft State, Eventually Consistent — trades strict consistency for performance and resilience.

- Use ACID for correctness-first systems (finance, booking, records).

- Use BASE for scale-first systems (feeds, catalogs, streams).

- Interview tip: Connect your answer to the CAP Theorem — ACID leans toward Consistency, BASE toward Availability.

- Modern hybrid trend: Databases like Spanner, CockroachDB, and YugabyteDB now blend both worlds.

🚀 What is the ACID Model in DBMS?

Think of ACID as the rulebook banks follow so your ₹10,000 transfer doesn’t vanish mid-flight.

ACID = Atomicity, Consistency, Isolation, Durability.

👉 Examples of ACID systems: MySQL, PostgreSQL, Oracle, SQL Server. Even some NoSQL DBs like CouchDB and IBM Db2 offer partial ACID compliance.

ACID — deep dive (the “safe and correct” squad)

1) Atomicity — all-or-nothing

What it is: A transaction must either complete fully or have no effect at all. No half-work allowed.

Real example: Money transfer:

BEGIN;

UPDATE accounts SET balance = balance - 100 WHERE id = 1;

UPDATE accounts SET balance = balance + 100 WHERE id = 2;

COMMIT;

-- if anything fails, ROLLBACK to leave both accounts as before

Developer insight / mini-story: Many teams forget to handle error paths and leave partial updates. The result? Phantom money. Atomicity prevents that but only within a single transaction boundary. Cross-service transfers (multiple microservices) can’t rely on a single DB transaction — you’ll need sagas or 2PC (two-phase commit) patterns. Sagas are usually preferred in microservices because 2PC is brittle and blocks resources.

Pitfalls to avoid: Long-running transactions, mixing DB-level transactions across services, assuming a queued message + DB update is “atomic” without handling partial failures.

Interview nugget: Be ready to explain how you’d implement a multi-step money transfer across services (compensating transactions, idempotency keys, or an orchestrator).

2) Consistency — rules stay true

What it is: When a transaction finishes, the database must move from one valid state to another, respecting all constraints (FKs, CHECKs, invariants).

Real example: If inventory quantity cannot be negative, the DB constrains that. An update either keeps invariants intact or the transaction is rejected.

Developer insight: Consistency is often implemented by schema constraints and triggers. But application-level logic can create additional invariants (e.g., “a user must not have two active subscriptions of type X”). Those invariants must be enforced carefully — either at DB level or with coordinated logic.

Pitfalls: Relying only on application checks (race windows) or enforcing invariants only in caches. Those create subtle bugs at scale.

Career tip: Interviewers like real examples: describe how you enforced business rules in a transaction and why schema-level constraints helped.

3) Isolation — transactions don’t step on each other

What it is: Concurrent transactions should have effects as if they executed serially. Practical DBs offer isolation levels that trade strictness for performance.

Common isolation levels (and the anomalies they allow):

- Read Uncommitted: Dirty reads allowed.

- Read Committed: No dirty reads; non-repeatable reads may occur.

- Repeatable Read: Prevents non-repeatable reads; phantom reads may still happen.

- Serializable: Full isolation; no anomalies but can be slow.

Real-world tie-in: PostgreSQL uses MVCC (multi-version concurrency control) to provide good isolation with low locking. MVCC is a career-worthy concept: it lets reads not block writes and vice versa.

Developer insight: Many bugs come from picking the wrong isolation level for the job. For example, analytics queries can use lower isolation; payment processing should aim for stricter levels.

Pitfalls: Choosing Serializable everywhere kills throughput; choosing Read Uncommitted for critical money transfers invites corruption.

Interview hook: Be able to describe dirty reads, non-repeatable reads, and phantom reads, and how MVCC mitigates them.

4) Durability — once committed, it stays committed

What it is: After a transaction commits, the result survives crashes, power loss, etc.

How DBs achieve it: Write-Ahead Logging (WAL), fsync to disk, replication, backups. The DB writes intent to log before applying changes so it can recover after a crash.

Real example: PostgreSQL’s WAL; MySQL’s InnoDB redo logs.

Developer insight: Durability has operational cost. Some systems choose to batch fsync or trade off durability for latency—be explicit about that trade-off.

Pitfalls: Relying only on a single replica; ignoring fsync behavior in cloud storage; failing to test restores regularly.

Ops/career tip: SREs and DBAs will grill you on backup/restore strategy and RPO/RTO — know them.

🛡️ ACID Best Practices for Developers

Mastering ACID isn’t just about knowing the letters — it’s about writing transactions that are safe, reliable, and performant. Here’s a practical set of rules to follow:

- Keep transactions short and focused

- Long-running transactions increase lock contention and reduce throughput.

- Only include operations that truly need to be atomic together.

- Use DB-level transactions, not ad-hoc sequences

- Let the database manage atomicity, isolation, and durability.

- Avoid splitting a single logical operation across multiple manual queries without transactional boundaries.

- Enforce critical invariants at the database level

- Foreign keys, unique constraints, and CHECK constraints protect your data integrity.

- Supplement with application-level checks only when necessary, not as a replacement.

- Handle distributed or cross-service operations carefully

- ACID only applies within a single database transaction.

- Use Sagas or idempotent compensating actions for multi-service workflows (e.g., transferring money across microservices).

- Choose isolation levels wisely

- Match the isolation level to the use case: Serializable for critical financial operations, Read Committed for analytics or reporting.

- Understand your DB’s default (PostgreSQL defaults to Read Committed).

- Plan for durability and recovery

- Configure WAL (Write-Ahead Logging) or equivalent for crash recovery.

- Use replication, backups, and test restore processes regularly.

- Be explicit about trade-offs: synchronous commit for strong durability, async for performance where acceptable.

⚡ What is the BASE Model in DBMS?

Now, picture Amazon on Black Friday. Millions of people hit “Add to Cart” at the same time. If Amazon stuck to ACID strictly, the site would crash. That’s where BASE comes in.

BASE = Basically Available, Soft State, Eventually Consistent.

👉 Examples of BASE systems: Cassandra, DynamoDB, MongoDB, Couchbase, Redis.

💡 Career insight: BASE dominates social media, streaming, IoT, large-scale e-commerce. If you want to work on distributed systems at FAANG-scale, you need to understand eventual consistency.

BASE — deep dive (the “scale and available” squad)

1) Basically Available — keep answering requests

What it is: The system aims to always respond, even in presence of node failures. Reads/writes may be served by different replicas.

Real example: Large e-commerce or social platforms replicate data across many nodes; if one partition fails, the system keeps serving, possibly with stale data.

Developer insight: Availability-first systems accept that responses might be slightly stale to avoid rejecting requests during failures. That’s a deliberate UX and engineering choice.

Best practices:

- Decide acceptable staleness for different endpoints (e.g., product catalogue vs. payment status).

- Provide eventual reconciliation mechanisms (background syncs).

- Monitor replication lag and alert when it exceeds SLA.

Pitfalls: Exposing stale critical data to users (e.g., showing a sold-out product as available) without clear UX handling.

2) Soft State — data is in flux

What it is: The system’s state can change over time without external input, due to asynchronous replication/correction processes.

Example: Caches, TTLs, or background processes (like read-repair) cause state to evolve. During replication, some nodes may temporarily hold diverging values.

Developer insight: Soft state is not a bug — it’s how distributed systems converge. But you must design the app to expect it.

Best practices:

- Make operations idempotent (retry-safe).

- Store versioning metadata (timestamps, vector clocks) to reason about staleness.

- Design UI/UX for “eventual truth” (show “last updated at” timestamps, or “may be delayed”).

Pitfalls: Treating cache copies as source of truth; assuming immediate convergence after writes.

3) Eventually Consistent — consistency promises, just later

What it is: The system guarantees that, given no new updates, all replicas will converge to the same state eventually.

How systems achieve it: background reconciliation (anti-entropy), hinted handoff, read repair, or CRDTs (Conflict-free Replicated Data Types) for automatic, mergeable updates.

Real example & pattern notes:

- Amazon Dynamo family introduced ideas like vector clocks and hinted handoff to reconcile divergent versions.

- Cassandra offers tunable consistency: you can require

QUORUMfor reads/writes to get stronger guarantees when you need them.

Developer insight: Accepting eventual consistency forces you to handle conflicts: choose conflict-resolution strategies (last-write-wins, custom merge logic, or CRDTs). Each has trade-offs:

- Last-write-wins (LWW): Simple, but can lose updates.

- CRDTs: More work upfront, but great for counters, sets, and merges without manual conflict resolution.

Best practices:

- Use causal or session consistency for user-facing flows where order matters (e.g., user posts).

- Expose consistency options (strong vs. eventual) to API consumers.

- Log and monitor conflict rates to refine your merge strategy.

Pitfalls: Not planning for conflict resolution, assuming eventual means “a few ms” (it can be seconds or longer under partition), or leaking inconsistency into financial operations.

Practical checklist — what to do in real systems

- If correctness matters (money, health): ACID — use RDBMS, strict transactions, backup/restore plans.

- If scale and availability matter (social feed, global catalog): BASE — design for eventual consistency, idempotency, and conflict resolution.

- Hybrid approach: Consider NewSQL or Spanner-like systems for global consistency at scale. Use services that offer tunable consistency (e.g., DynamoDB, Cassandra).

- Always: document invariants, add observability around replication lag, and design UX to communicate staleness.

Mistakes developers keep making (and how to avoid them) ⚠️

- Mistake: Treating cached or secondary replicas as authoritative.

Fix: Always consider lineage/version and surface “last-updated” times. - Mistake: Assuming ACID boundaries span microservices.

Fix: Use Sagas or event-driven compensation. - Mistake: No conflict-resolution plan for BASE.

Fix: Choose LWW, CRDTs, or business logic merges based on data type.

Career & interview angle 🎯

- Expect system-design prompts like “Design a ticketing system — ACID or BASE?” Answer with trade-offs, propose patterns (Sagas, CRDTs, quorum reads) and show awareness of isolation levels and WAL.

- Knowing practical tools matters: Postgres / MySQL / Oracle for ACID; Cassandra / DynamoDB / MongoDB for BASE; NewSQLs (CockroachDB, Yugabyte) for hybrid needs.

- Add these to your resume with short bullets showing real outcomes: “Reduced double-charges by implementing transactional compensation using sagas” — concrete results beat theory.

🔄 ACID vs BASE: Key Differences

Here’s the ultimate side-by-side snapshot:

| Feature | ACID (RDBMS) | BASE (NoSQL/Distributed) |

|---|---|---|

| Consistency | Strong, immediate | Eventual, relaxed |

| Availability | Limited under failures | High, even under failures |

| Scaling | Vertical (bigger server) | Horizontal (more servers) |

| Use cases | Banking, healthcare | Social media, e-commerce |

| Examples | MySQL, Oracle, PostgreSQL | Cassandra, DynamoDB, MongoDB |

⚠️ Don’t memorize this table blindly. In interviews, recruiters often ask: “When would you NOT use ACID?” or “Why does BASE matter for scalability?” That’s your chance to shine.

🧑💻 Real-World Use Cases

- ACID in Action:

- Bank transfer between two accounts

- Hospital patient record updates

- Airline seat booking

- BASE in Action:

- Instagram showing you likes in near real-time

- Amazon shopping cart during peak sales

- Netflix video recommendations syncing slowly

💡 Best Practices for Developers

- ✅ Choose ACID when: You need trust, correctness, and reliability (finance, government records, healthcare).

- ✅ Choose BASE when: You need scalability, high availability, and speed (social networks, e-commerce).

- ⚠️ Mistake to Avoid: Forcing ACID rules on a massive NoSQL cluster. You’ll kill performance.

- ⚠️ Another Mistake: Blindly choosing BASE without planning for eventual consistency. Your users may see “weird” states.

👉 Pro tip for interviews: Always frame your answer around the CAP theorem. ACID leans toward Consistency, BASE leans toward Availability.

🌍 Modern Hybrid Models

The story doesn’t end with ACID vs BASE. Modern databases try to balance both:

- Google Spanner → global transactions with strong consistency.

- CockroachDB, YugabyteDB (NewSQL) → ACID-compliant but scale like NoSQL.

🔥 These are hot in startups and enterprises. Knowing them can make you stand out.

✨ Conclusion

Let me put it this way: ACID is your cautious banker, BASE is your speedy shopkeeper. Both are essential in today’s tech ecosystem. They’re not enemies, they’re trade-off tools. Below is a focused, practical breakdown of Atomicity, Consistency, Isolation, Durability (ACID) and Basically Available, Soft State, Eventually Consistent (BASE) — each explained, with examples, pitfalls, best practices, and career tips. 🚀

If you’re preparing for system design interviews or aiming to work on high-scale distributed systems, don’t just memorize these models. Think about the trade-offs. That’s what separates a good developer from a great one.

And if you want to go deeper, read CAP Theorem explained on IBM Docs.

Related Reads

Explore these articles to deepen your understanding of software design, algorithms, and operating systems:

- Design Patterns in C# & Java (2025 Guide) – With Code Examples, UML & Best Practices

Learn how to implement essential design patterns in C# and Java, complete with code examples and UML diagrams, tailored for modern software development. - 5 Creational Design Patterns in Java Software Design Patterns (Explained With Real Examples)

Get a deep dive into 5 key creational design patterns in Java, including real-world examples to enhance your understanding of object creation mechanisms. - Understanding OS Types: Desktop, Server, and Mobile OS Types Explained

A comprehensive guide to understanding different operating system types—desktop, server, and mobile—and how they are optimized for specific use cases. - Design and Analysis of Algorithms – A Complete Guide

Master the foundations of algorithm design and analysis, and explore how to optimize algorithms for performance and efficiency.